THE TRAGIC LIFE OF MARGARET POLE

Margaret Pole was born on

14 August 1473. She was the daughter of George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence.

George was a pesky middle child, born between two Kings of England, Edward IV

and Richard III. George was never satisfied in life, constantly wanting more

while feeling as though what he had wasn’t enough. George was a changeable character,

often aligning with those who would satiate his hunger for ambition. George

assisted his brother, King Edward IV to the throne, but turned to the

Lancastrians when Edward IV refused to allow him more lands, power and advantageous

marriages. George assisted his cousin, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, known

to history as the Kingmaker, depose Edward IV and return King Henry VI to the

throne during the period now known as the Readeption. Edward IV took back his throne and brought George back on side, always keeping one eye on him.

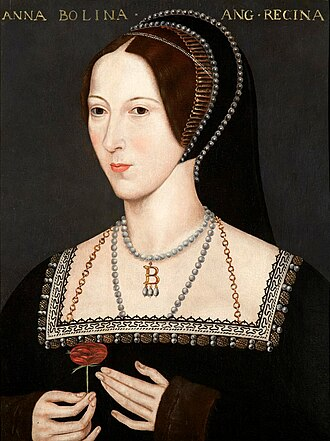

Portrait of an Unknown Woman, thought to be Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, Unknown, c. 1535

The final straw for Edward

IV occurred when George attempted to marry Mary, Duchess of Burgundy. Edward IV

could not allow this marriage to take place as it would deliver George the

power and means to intensify the rebellions he had already put in place. George

was eventually arrested for treason and, allegedly, was executed by drowning in

a barrel of Malmsey wine. Margaret lost her father at the age of 5. She wore a

bracelet throughout her life, of which dangled a wine barrel charm, perhaps in

remembrance of her father, giving the story a particular amount of credence.

Margaret’s maternal grandfather, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, stayed on side with the Lancastrians and was killed at the Battle of Barnet on 14 April 1471.

More tumultuous times

would follow. Margaret’s uncle, Edward IV died in February 1478. Margaret’s

cousin, Edward V, should have become King, but her uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester,

had Edward V and his brother Richard, declared illegitimate. This left the

throne wide open for Richard to take, as Margaret’s brother, Edward, was barred

from the throne because of the Act of Attainder that was passed against their

father, George. Margaret would have witnessed her uncle become King Richard III.

Tragedy would strike Margaret again, when her cousins, Edward V and Richard,

Duke of York, were held in the Tower of London, never to be seen again. They

would become known to history as the Princes in the Tower.

At this point, Margaret’s life was in constant limbo. However, the crown was still in her family. That would all change on 22 August 1485, when Henry Tudor invaded England and killed Margaret’s uncle, Richard III, at the Battle of Bosworth. Henry Tudor became King Henry VII. This had its pros and cons for Margaret. Elizabeth of York, her cousin, married Henry VII and became Queen of England. Elizabeth of York was always in Margaret’s corner, fighting her for family when she could. However, this meant that the crown was no longer in the York family. It made Margaret and her brother Edward claimants to the throne of England. Rivals would be exactly how Henry VII viewed the Plantagenet siblings.

While Margaret remained

free, Edward was imprisoned at the Tower of London at only 10 years old. He

would remain there for the next fourteen years. After multiple pretenders to

the throne, rebellions, and an ultimatum from the Spanish Monarchy, Edward

Plantagenet, Earl of Warwick, was found guilty of treason. He was executed on

28 November 1499 on Tower Hill. Margaret, already an orphan, lost her only sibling.

That happiness would be

ripped from Margaret in 1505, when Richard Pole died. She was now a widow, without

income, and five children to care for. Bereft, Margaret would give her son,

Richard Pole, to the church. Richard Pole would go on to have an extraordinary career

in the church, but would become a thorn in the backside of King Henry VIII, which

would ultimately lead to Margaret’s demise.

Things began to look up

for Margaret in 1509 when Henry VII died and his son assumed the throne as King

Henry VIII. Margaret was appointed as Queen Catherine of Aragon’s lady in

waiting, possibly a tribute to their time together, when Margaret cared for

Catherine when she was first married to Henry VIII’s brother, Arthur Tudor. In 1512,

Margaret extraordinarily was restored to her rightful inheritance from her

father, as Countess of Salisbury, in her own right. She was only one of two

women who held that right in the 16th century. By 1538, Margaret was

one of the wealthiest in England.

But, as the wheel of fortune is constantly turning in 16th century England, Margaret would not stay in favor for long. Remember her son I told you about- Reginald Pole? He became so irksome to Henry VIII, over on the continent, opposing the divorce from Queen Catherine of Aragon and vehement against the King’s relationship with Anne Boleyn. Later, the Exeter Conspiracy would come to light, which sought to remove Henry VIII from power after his break from the Roman Catholic Church. Margaret’s son, Geoffrey Pole, was arrested and brought in for questioning. Geoffrey confessed that he and his family had corresponded with his brother Reginald about this plot. This made Reginald Pole public enemy number one. Margaret, her son, Henry Pole, Lord Montagu, and Henry Courtenay, Marquess of Exeter, were all arrested on charges of treason in November 1538. All three were found guilty and sentenced to death.

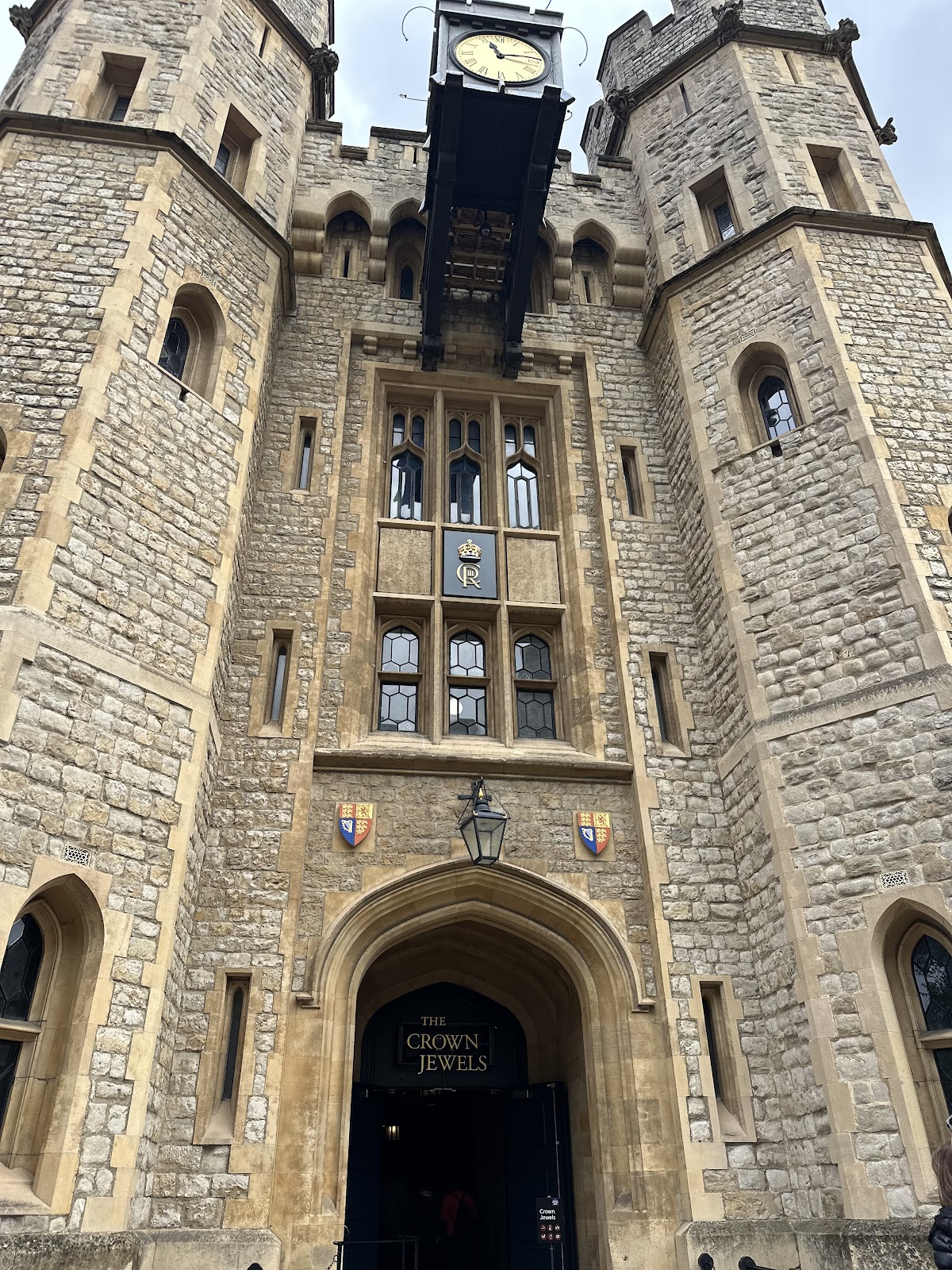

Margaret was held in the

Tower of London for two and half years. On the morning of 27 May 1541, she was

taken to the scaffold. Margaret suffered the worst beheading, in that the

inexperience axe man, it was said, took eleven strokes to complete the

execution. According to the Imperial Ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, the main executioner

had been sent north to deal with rebels. She was 67 years old and arguably the

worst of many stains during Henry VIII’s reign. Margaret was laid to rest in

the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London.

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, Memorial Plaque in the Chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London, © All Things Tudors, May 2023

On 29 December 1886, Pope

Leo XIII beatified Margaret Pole as a Catholic martyr. Her son, Reginald Pole,

would serve Queen Mary I as the last Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury.